Crafted in Confinement: The Bilibid Prison Peacock Chair

Wings Behind Bars: The Fascinating Story of the Peacock Chair from Bilibid Prison While browsing through my old photo album, I came across a picture of my 6-month-old self sitting in a rattan chair, looking instantly familiar. It was a child’s peacock chair—one of the many variations of the Peacock Chair that once became a […]

Crafted in Confinement: The Bilibid Prison Peacock Chair

Wings Behind Bars: The Fascinating Story of the Peacock Chair from Bilibid Prison

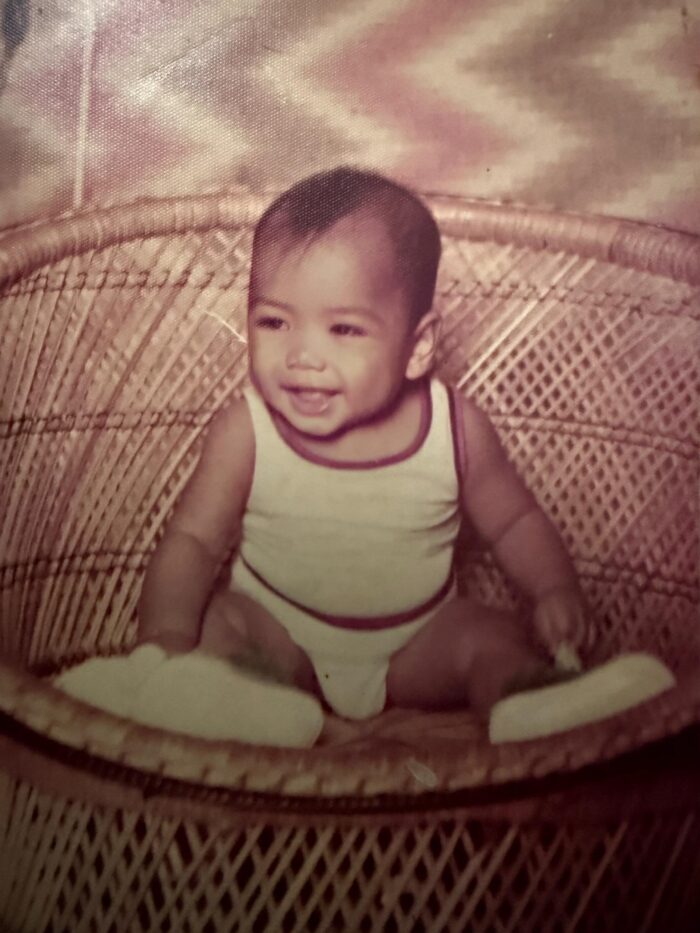

While browsing through my old photo album, I came across a picture of my 6-month-old self sitting in a rattan chair, looking instantly familiar. It was a child’s peacock chair—one of the many variations of the Peacock Chair that once became a popular export from the Philippines.

A photo of me at 6 months old.

I have always been drawn to objects that offer more than beauty—objects that whisper stories through their curves, textures, and imperfections. Some pieces speak of luxury, others of tradition and indigenous artistry.

But every so often, you encounter an artifact so layered with history, resilience, and quiet defiance that it lingers in your mind long after you’ve seen it. The Peacock Chair, crafted inside Bilibid Prison in the Philippines, is one such masterpiece, and finding a photo of myself sitting in it made me appreciate its craftsmanship even more.

Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton on a peacock chair, in a 1967 portrait photograph by Blair Stapp

At first glance, the Peacock Chair is undeniably striking. Its fan-shaped back unfurls like the plumage of a peacock in full display—dramatic, proud, and almost regal. Woven from rattan meticulously bent and tied into an elaborate sunburst of loops and spindles, the chair appears light, airy, and ornamental, yet it commands attention.

What made this chair truly special was not its design or material. What most people don’t realize, however, is that this symbol of elegance was born behind prison walls, crafted by inmates.

The Setting: Bilibid Prison

Bilibid Prison, officially known as the New Bilibid Prison, occupies a complex place in Philippine history. Established in the Spanish colonial period and expanded under American rule, it functioned not only as a site of incarceration but also as an unexpected center of craftsmanship. By the early to mid-20th century, prison authorities had introduced vocational programs that taught inmates trades such as carpentry, shoemaking, metalwork, and, most notably, furniture making.

Among these programs, rattan weaving proved especially successful. Blessed with abundant rattan vines, the Philippines has long nurtured traditions of basketry and furniture-making. Inside Bilibid, this craft provided inmates with both income and a vital psychological outlet. Through the steady, repetitive motions of weaving, many prisoners found solace, purpose, and a measure of dignity otherwise stripped away by confinement.

Peacock Chair from Bilibid

The Birth of the Peacock Chair

The Peacock Chair emerged during the American colonial era, roughly between the 1910s and 1930s—a period when Western tastes increasingly intertwined with Filipino craftsmanship. Its exact origins are difficult to pinpoint; the design likely evolved gradually through many hands rather than from a single known creator. What we recognize today as the Peacock Chair is the result of this slow collaboration, combining indigenous weaving traditions with the bold geometry and stylized elegance of the Art Deco movement that was popular at the time.

Its iconic peacock silhouette was far more than decoration. The tall, fanned backrest—spreading outward like a bird’s tail in full display—demanded exceptional skill and control over rattan, a material that is both resilient and temperamental. To achieve those radiating arcs, each strand had to be carefully soaked, bent into a precise curve without snapping, then dried and secured by hand. The seat, base, and bordering patterns added more layers of complexity, often featuring lattices, loops, and subtle motifs that shifted with light and shadow, making the chair feel almost sculptural. Depending on the intricacy of the design, a single Peacock Chair could take several days to several weeks to complete.

The inmates who crafted these chairs were not simply workers but highly trained artisans. They spent years learning to understand the grain and temperament of rattan—how far it could be pushed into sweeping curves, how tightly it could be woven before losing flexibility. Only after mastering simpler furniture forms were they entrusted with the Peacock Chair, whose broad, halo-like backrest required a balance of technical precision and artistic sensitivity.

A particularly compelling aspect of the Peacock Chair is that no two pieces are exactly alike. Even when following the same general pattern, each artisan left subtle traces of individuality: a slightly different spacing of the fan’s ribs, a distinct rhythm in the weave, or a unique emphasis in the back’s curvature. These slight irregularities become personal marks, quiet signatures hidden in plain sight. In this sense, every chair carries a muted but powerful assertion of the maker’s identity—an enduring, handmade testament from someone the outside world knew only as a number.

From Prison Workshops to Presidential Palaces

Perhaps the most astonishing chapter in the Peacock Chair’s story is its journey beyond prison walls. These chairs did not remain obscure prison products. Instead, they found their way into elite homes, hotels, and government buildings.

Most famously, Peacock Chairs were used in Malacañang Palace, the official residence of the Philippine president. Vintage photographs show dignitaries and first ladies seated regally against the dramatic halo of woven rattan—a powerful visual contrast when one considers the chair’s origins. What was once made by incarcerated men became a symbol of tropical sophistication and Filipino craftsmanship at its finest.

The chair also gained international recognition. As rattan furniture became fashionable in Europe and the United States, Peacock Chairs were exported and admired abroad. Many collectors today are surprised to learn that prized antique examples trace their roots back to Bilibid Prison workshops.

Symbolism Woven into Form

The peacock is a powerful symbol of pride, beauty, immortality, and rebirth. Whether intentional or subconscious, choosing this form feels deeply poetic. For inmates, patiently crafting a bird-shaped chair on public display may have been an act of quiet hope—a metaphorical stretching of wings within the strict limits of their imprisonment.

As I study vintage Peacock Chairs, I’m struck by how their airy, intricate weave lets light and air pass through in delicate patterns. Unlike solid wood thrones, these chairs do not impose heaviness or authority; they seem to breathe, to invite. Their openness feels almost tender, as if the structure itself were designed to welcome rather than command. Perhaps this transparency reflects the emotional release that crafting offered the inmates—a brief, hard-won sense of freedom expressed through form and negative space.

Marguerite Carmack in jeweled crown and costume, sitting in a wicker fan chair, Seattle, Washington, ca 1910

Craftsmanship and Technique

Technically, the Peacock Chair is a marvel of rattan craftsmanship. It depends on rattan’s natural flexibility, yet demands a keen sense of tension, balance, and structural integrity. The dramatic backrest, though delicate in appearance, must safely support weight.

Traditionally crafted entirely by hand and without nails or screws, Peacock Chairs were bound with thin rattan strips or natural-fiber ties. As rattan ages, its honey color deepens with exposure, creating a warmth and character that many modern reproductions can’t match.

Original Bilibid-made chairs tend to be heavier and more tightly woven than today’s versions, reflecting a clear focus on durability. They were never mass-produced; each one was a patient, painstaking creation.

The Modern Raina Peacock Chair by Vito Selma, photo by Bim24 – Own work, CC0

The Human Story Behind the Chair

What moves me most, as a journalist and craft lover, is the human narrative embedded in each curve. The Peacock Chair challenges our assumptions about where beauty comes from. It reminds us that artistry can flourish even in the harshest environments.

For inmates, crafting these chairs was not just about earning a livelihood—it was about reclaiming humanity. In a system designed to punish, the act of making something beautiful became an act of resistance. The chairs carried none of the bitterness one might expect; instead, they radiate grace.

There is a quiet irony here. Many of the people who sat in these chairs lived lives of privilege and power, unaware—or only vaguely aware—that the seat beneath them was woven by hands deprived of freedom. Yet perhaps that contrast is what gives the Peacock Chair its enduring power.

Legacy and Modern Appreciation

Today, the Peacock Chair enjoys a revival in popularity, especially in bohemian, tropical, and mid-century-inspired interiors. Designers and influencers embrace its dramatic silhouette, often unaware of its profound history. While modern versions are widely available, antique Bilibid-made chairs are increasingly sought after by collectors who appreciate both their craftsmanship and cultural significance.

Museums, historians, and Filipino artisans are now working to reclaim and tell this story more openly. The chair is no longer just a decorative object; it is a cultural artifact—a reminder of colonial history, prison reform, and the resilience of Filipino creativity.

The Peacock Chair

A Chair That Speaks

In the end, the Peacock Chair does not simply sit in a room—it watches, remembers, and endures. Its woven wings hold the silence of prison corridors, the scrape of rattan against concrete floors, the steady breath of men who poured patience into every curve. It is a throne without a king, a bird that learned how to fly without ever leaving the ground.

To sit in a Peacock Chair is to unknowingly enter a conversation with its maker. You feel it in the gentle give of the weave, in the halo that frames your head like borrowed plumage. It reminds us that beauty is not always born of freedom, but of longing—and that even behind walls meant to contain the body, the human spirit finds ways to spread its feathers.

Long after the prison gates close and the workshop falls quiet, the Peacock Chair remains—unconfined, unapologetic, and breathtaking—proof that art, once released into the world, can never truly be imprisoned.

Manila Travel Tour Packages You Should Try

<script type="text/javascript"></p> <p> (function (d, sc, u) {</p> <p> var s = d.createElement(sc),</p> <p> p = d.getElementsByTagName(sc)[0];</p> <p> s.type = "text/javascript";</p> <p> s.async = true;</p> <p> s.src = u;</p> <p> p.parentNode.insertBefore(s, p);</p> <p> })(</p> <p> document,</p> <p> "script",</p> <p> "https://affiliate.klook.com/widget/fetch-iframe-init.js"</p> <p> );</p> <p></script>

Follow and subscribe to OutofTownBlog.com on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and YouTube for more Travel-related updates.

Read: This group of Tagbanwa women showcases handicraft weaving skills to keep traditions alive

Crafted in Confinement: The Bilibid Prison Peacock Chair

The post Crafted in Confinement: The Bilibid Prison Peacock Chair appeared first on Out of Town Blog

Comments and Responses

Please login. Only community members can comment.